White Wahalla - an excerpt

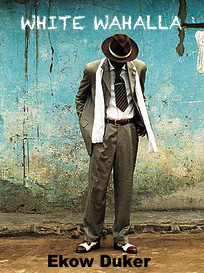

The man sat alone in the wooden kiosk. He was impeccably dressed as always in neat dark trousers and a loose matching jacket. Broad patterned stripes flowed in obedient lines down his crisply starched shirt. A pair of heavy silver cufflinks on his wrists glinted evilly in the lamplight. They looked like the eyes of a large rodent crouched among the papers on the desk. And when he bent his large head to study the neat handwritten entries in his ledger, the tip of his tie hovered inches above the page. His name was Cash Tshabalala and he was a moneylender. By his own admission he was the most notorious moneylender in Scottsville. And just like a modern day celebrity, he went by his first name only. Cash. Outside on the roof of his kiosk a flashing red neon sign brashly declared that his was “The Last Best Hope Financial Service”. The stylised letters ended with a diagonal arrow that pointed down to the metal door with a brass knob in the shape of a baboon’s skull.

Cash Tshabalala was as black as the bottom of a cast iron cooking pot. A fold of skin clung to the back of his head and formed a thick ridge above his collar. He always dressed formally and preferred his ties in flamboyant colours with psychedelic designs that writhed across his chest like angry snakes. In a town where many were forced to wear second hand clothes, Cash Tshabalala’s sleek attire added powerfully to his aura. He spent most of his time in his kiosk, arriving every morning before seven. He left late at night when the women who prepared evening meals at the side of the road had gone home themselves.

His credit decisions were surprisingly swift. They involved nothing more than a brief interview in which Cash Tshabalala said very little. He would simply dominate the small space with his imposing presence and glower at the prospective borrower as if he had brought a bad smell into his kiosk. Once the applicant had nothing more to say, an awkward silence would settle over the pair. It went on until either Cash Tshabalala pulled open a drawer and counted out the money or motioned with his eyes for the applicant to leave. It did no good to plead with Cash. He was not that sort of man. In the township they said that if Cash Tshabalala lent you money, you were just as likely to be afraid as relieved.

Defaulters were punished with an unbridled savagery that left many with broken limbs and battered faces, regardless of age or sex. Not long ago Cash and his boys beat old Mr. Kubeka so badly that the poor man forgot his own name. Later a crowd of indignant protestors gathered outside the kiosk shouting slogans in solidarity with Mr. Kubeka. Cash came out and stood in the door of his kiosk. Then without saying a word, he simply pointed in turn at all those in the crowd who owed him money. Unfortunately that happened to be most of those present. One by one they slunk away, cowering like the stray dogs that lived in the marshes on the edge of Scottsville. It was better, they decided, to leave old Mr. Kubeka to fight his battles on his own.

A loud knock on the door broke the silence in the kiosk and made the framed picture of South Africa’s portly president jiggle uncontrollably on the wall. Cash looked up with a frown. That had to be his sister Gladys. She barged in without waiting to be invited and sat down with a thump. She wore an elaborate scarf on her head. It was made of several folds of West African cotton that tapered upwards from her head before erupting in a burst of riotous colour.

Cash grunted without looking up at his sister. “You’ve come.”

Gladys nodded. They both knew why she was there, but she proceeded to tell Cash anyway.

“They’ve started harvesting tomatoes up north,” she said.

“I know.” Despite his better judgement Cash found himself responding to his sister’s rapid chatter. She knew him too well and his trademark silent treatment had no effect on her.

“I need six thousand rand to buy tomatoes for my market stall,” she declared boldly. “Remember you lent me the same amount last year.”

“Not this year Gladys.”

“Heh?”

Gladys was the only one who could talk back at Cash. She stood up abruptly with her hands on her hips and the tassels of her scarf almost brushed against the ceiling.

“I paid you back didn’t I? With interest.”

Cash blinked his eyes slowly in acknowledgement before replying.

“There was a bumper tomato harvest this year,” he said slowly. “Everyone and their dog will be selling tomatoes.”

Gladys snorted in disgust. “Since when did you know anything about tomatoes Cash?”

“I’m not lending money for tomatoes this year,” he said firmly. “It’s not good business.” He motioned with a slight inclining of his head for Gladys to leave and her eyes narrowed to dark slits.

“Why Cash?” she asked. There was a hint of irritation in her voice. “You’ve lent me money every year for as long as I can remember.”

“Not this year Gladys. Not for tomatoes.”

Gladys’ chest heaved under the brightly coloured fabric.

“Can’t you do something small?” she whined, immediately despising the desperation in her voice.

Cash shrugged and lay both palms open on the table. “Try the bank,” he said with as much kindness as he could muster; which in reality was very little.

Gladys snatched up her handbag and tucked it under her armpit as if it were a small child. She stopped at the door and turned towards her brother.

“The bank won’t lend me any money and you know why?” Her voice was strangely calm and without any emotion. Cash cringed in his chair. He knew what she was about to say. She pulled a crumpled form from her bag and tossed it across the desk towards Cash. It had Megabank’s violet logo in one corner followed by rows of neat lines, symmetrical boxes and very small print. Cash picked it up and squinted hard at the red stamp running diagonally across the sheet.

“Look at that! They threw out my application again.”

“Declined?”

Gladys nodded bitterly. “And just because I’m your sister.” With that she squeezed through the doorway and clattered down the stairs without even bothering to say goodbye.

Cash sighed. She didn’t get it did she? Business was business and tomatoes were not good business this year. He rearranged the papers on his desk into a neat pile and carefully peeled off the topmost sheet. It was a short handwritten list of all those who owed him money and ranked in order of delinquency. Pastor Joel Mazibuko’s name was first on the list, followed by Oupa Sithole the builder.

Earlier this year and just before demand for residential housing collapsed spectacularly, Oupa borrowed seven thousand three hundred rand from Cash to buy a second-hand cement mixer. Now with no work in sight, Oupa had fallen behind on his payments. Nonetheless Cash was glad to see that Oupa wasn’t first on the list. He liked the little man with his wizened features and hard flinty eyes. Oupa understands business Cash said to himself. He’ll make a plan. There aren’t many men left like Oupa, he muttered. On the other hand, there are too many men like Pastor Mazibuko.

Cash’s cell phone howled plaintively once and then stopped. That meant S’bu One and S’bu Two were outside. Cash pushed the desk away from him and rose smoothly to his feet. He was surprisingly agile for such a big man. He stopped to adjust his tie in the mirror and pulled the knot even tighter until the skin of his neck folded over his collar like a roll of dough. He placed a black knitted skullcap on his head and patted it down until the delicate crochet stitches appeared to melt into his dark skin.

S’bu One and S’bu Two were standing attentively by the car. It was a white 1990’s Jaguar with bare wires in place of the ignition key. Otherwise it was a well kept machine and still drew cries of admiration throughout Soweto. S’bu Two nudged his brother and whispered, “Somebody’s in kak.” S’bu one nodded grimly in agreement.

The twins had been at Cash Tshabalala’s side ever since they were children in the Mission School in Dobsonville. Abandoned by their mother, Cash became the boys’ protector and over time they became his. Both were tall and muscular with oddly fashionable seventies style afros and sideburns that swooped defiantly across each cheek in a thin tapered line. They had that look of barely suppressed violence about them that attracted women like winged termites to a light bulb. The twins were so alike that in the Mission School their real names were forgotten. Sibusiso and Sibongile Hlatshwayo very quickly become S’bu One and S’bu Two.

S’bu Two touched the ignition wires together and the heavy vehicle coughed and stuttered into life. He glanced up at the rear view mirror. It was barely large enough to contain Cash Tshabalala’s brooding reflection.

“Where to, Boss?” His hand hovered expectantly above the polished gear lever, waiting patiently for Cash’s instructions.

“Pastor Mazibuko,” replied Cash softly and the Jaguar sprang forward like a demon unleashed.

Cash Tshabalala was as black as the bottom of a cast iron cooking pot. A fold of skin clung to the back of his head and formed a thick ridge above his collar. He always dressed formally and preferred his ties in flamboyant colours with psychedelic designs that writhed across his chest like angry snakes. In a town where many were forced to wear second hand clothes, Cash Tshabalala’s sleek attire added powerfully to his aura. He spent most of his time in his kiosk, arriving every morning before seven. He left late at night when the women who prepared evening meals at the side of the road had gone home themselves.

His credit decisions were surprisingly swift. They involved nothing more than a brief interview in which Cash Tshabalala said very little. He would simply dominate the small space with his imposing presence and glower at the prospective borrower as if he had brought a bad smell into his kiosk. Once the applicant had nothing more to say, an awkward silence would settle over the pair. It went on until either Cash Tshabalala pulled open a drawer and counted out the money or motioned with his eyes for the applicant to leave. It did no good to plead with Cash. He was not that sort of man. In the township they said that if Cash Tshabalala lent you money, you were just as likely to be afraid as relieved.

Defaulters were punished with an unbridled savagery that left many with broken limbs and battered faces, regardless of age or sex. Not long ago Cash and his boys beat old Mr. Kubeka so badly that the poor man forgot his own name. Later a crowd of indignant protestors gathered outside the kiosk shouting slogans in solidarity with Mr. Kubeka. Cash came out and stood in the door of his kiosk. Then without saying a word, he simply pointed in turn at all those in the crowd who owed him money. Unfortunately that happened to be most of those present. One by one they slunk away, cowering like the stray dogs that lived in the marshes on the edge of Scottsville. It was better, they decided, to leave old Mr. Kubeka to fight his battles on his own.

A loud knock on the door broke the silence in the kiosk and made the framed picture of South Africa’s portly president jiggle uncontrollably on the wall. Cash looked up with a frown. That had to be his sister Gladys. She barged in without waiting to be invited and sat down with a thump. She wore an elaborate scarf on her head. It was made of several folds of West African cotton that tapered upwards from her head before erupting in a burst of riotous colour.

Cash grunted without looking up at his sister. “You’ve come.”

Gladys nodded. They both knew why she was there, but she proceeded to tell Cash anyway.

“They’ve started harvesting tomatoes up north,” she said.

“I know.” Despite his better judgement Cash found himself responding to his sister’s rapid chatter. She knew him too well and his trademark silent treatment had no effect on her.

“I need six thousand rand to buy tomatoes for my market stall,” she declared boldly. “Remember you lent me the same amount last year.”

“Not this year Gladys.”

“Heh?”

Gladys was the only one who could talk back at Cash. She stood up abruptly with her hands on her hips and the tassels of her scarf almost brushed against the ceiling.

“I paid you back didn’t I? With interest.”

Cash blinked his eyes slowly in acknowledgement before replying.

“There was a bumper tomato harvest this year,” he said slowly. “Everyone and their dog will be selling tomatoes.”

Gladys snorted in disgust. “Since when did you know anything about tomatoes Cash?”

“I’m not lending money for tomatoes this year,” he said firmly. “It’s not good business.” He motioned with a slight inclining of his head for Gladys to leave and her eyes narrowed to dark slits.

“Why Cash?” she asked. There was a hint of irritation in her voice. “You’ve lent me money every year for as long as I can remember.”

“Not this year Gladys. Not for tomatoes.”

Gladys’ chest heaved under the brightly coloured fabric.

“Can’t you do something small?” she whined, immediately despising the desperation in her voice.

Cash shrugged and lay both palms open on the table. “Try the bank,” he said with as much kindness as he could muster; which in reality was very little.

Gladys snatched up her handbag and tucked it under her armpit as if it were a small child. She stopped at the door and turned towards her brother.

“The bank won’t lend me any money and you know why?” Her voice was strangely calm and without any emotion. Cash cringed in his chair. He knew what she was about to say. She pulled a crumpled form from her bag and tossed it across the desk towards Cash. It had Megabank’s violet logo in one corner followed by rows of neat lines, symmetrical boxes and very small print. Cash picked it up and squinted hard at the red stamp running diagonally across the sheet.

“Look at that! They threw out my application again.”

“Declined?”

Gladys nodded bitterly. “And just because I’m your sister.” With that she squeezed through the doorway and clattered down the stairs without even bothering to say goodbye.

Cash sighed. She didn’t get it did she? Business was business and tomatoes were not good business this year. He rearranged the papers on his desk into a neat pile and carefully peeled off the topmost sheet. It was a short handwritten list of all those who owed him money and ranked in order of delinquency. Pastor Joel Mazibuko’s name was first on the list, followed by Oupa Sithole the builder.

Earlier this year and just before demand for residential housing collapsed spectacularly, Oupa borrowed seven thousand three hundred rand from Cash to buy a second-hand cement mixer. Now with no work in sight, Oupa had fallen behind on his payments. Nonetheless Cash was glad to see that Oupa wasn’t first on the list. He liked the little man with his wizened features and hard flinty eyes. Oupa understands business Cash said to himself. He’ll make a plan. There aren’t many men left like Oupa, he muttered. On the other hand, there are too many men like Pastor Mazibuko.

Cash’s cell phone howled plaintively once and then stopped. That meant S’bu One and S’bu Two were outside. Cash pushed the desk away from him and rose smoothly to his feet. He was surprisingly agile for such a big man. He stopped to adjust his tie in the mirror and pulled the knot even tighter until the skin of his neck folded over his collar like a roll of dough. He placed a black knitted skullcap on his head and patted it down until the delicate crochet stitches appeared to melt into his dark skin.

S’bu One and S’bu Two were standing attentively by the car. It was a white 1990’s Jaguar with bare wires in place of the ignition key. Otherwise it was a well kept machine and still drew cries of admiration throughout Soweto. S’bu Two nudged his brother and whispered, “Somebody’s in kak.” S’bu one nodded grimly in agreement.

The twins had been at Cash Tshabalala’s side ever since they were children in the Mission School in Dobsonville. Abandoned by their mother, Cash became the boys’ protector and over time they became his. Both were tall and muscular with oddly fashionable seventies style afros and sideburns that swooped defiantly across each cheek in a thin tapered line. They had that look of barely suppressed violence about them that attracted women like winged termites to a light bulb. The twins were so alike that in the Mission School their real names were forgotten. Sibusiso and Sibongile Hlatshwayo very quickly become S’bu One and S’bu Two.

S’bu Two touched the ignition wires together and the heavy vehicle coughed and stuttered into life. He glanced up at the rear view mirror. It was barely large enough to contain Cash Tshabalala’s brooding reflection.

“Where to, Boss?” His hand hovered expectantly above the polished gear lever, waiting patiently for Cash’s instructions.

“Pastor Mazibuko,” replied Cash softly and the Jaguar sprang forward like a demon unleashed.