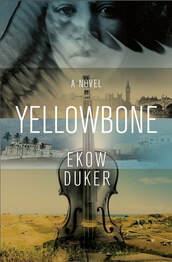

Yellowbone- an excerpt

Precious knocked on the door and when she entered she found Jabu Molefe seated cross-legged on the bare floor. He was still in his blue overalls, the ones with yellow reflective stripes around the elbows and ankles. He looked more like the municipal labourer he was than a man who wrestled daily with spirits and imparted wisdom to all comers. There was a straw mat spread out in front of him and on it were neat bunches of herbs tied with blades of dried grass, an assortment of coloured beads and an enamel cup half full of water.

Precious felt a little cheated that Jabu hadn’t bothered to change out of his overalls. The last time she’d seen him he’d been wearing a grass skirt with leather amulets tied around his biceps. At least he could have messed up his hair a little.

‘You have come.’

His voice was deep and resonant, just how igqirha’s voice should be.

Precious smiled. Perhaps she’d get her money’s worth after all.

‘What brings you here, my daughter?’

She wished Jabu wouldn’t call her that. He'd been two classes behind her at school. She shut her eyes and tried to focus on the fact that he was igqirha now, at least when he wasn’t cutting grass for the municipality.

‘You know why I am here. It is my husband.’

She thought his eyes glimmered but it was difficult to tell in the half light.

‘The teacher?’

‘Yes – Teacher. My husband.’

Jabu bent his head and stirred the beads with a dry twig. Then he dipped his hand into the cup of water and, without warning, flicked his fingers at Precious. She recoiled and cried out in alarm, feeling strangely humiliated, as if he had spat at her. But she did not dare wipe her face.

‘Does he know you?’

‘What do you mean, Jabu? He is my husband. Of course he knows me.’

Jabu slipped his hand between his legs and cupped his crotch.

‘My daughter, I asked whether your teacher knows you.’

Precious’s face burned with shame at the turn Jabu’s questions had taken.

‘No, Jabu,’ she said quietly. ‘Not for several months.’

He bent his head again and rummaged among the items on the mat. His hands were dry and covered in small scars. He muttered a few words to himself, then handed Precious a brown kidney-shaped nut.

‘Eat,’ he said,

Precious reached across and took the nut from him, taking care not to let her hand touch his. When she bit into it a peppery taste flooded her mouth. Jabu watched her carefully until she had swallowed the last piece.

‘I see the cause of your troubles, my daughter.’

‘Tell me,’ she said eagerly.

‘It is a woman.’

What woman? Did Teacher have a girlfriend? Precious ran through the women she’d seen around Teacher, scoring them against their likelihood of mischief. She didn’t trust Dorothy Mpetla. The bitch read the notices in church and spoke isiXhosa like an Englishwoman, clicking her tongue in all the wrong places. But it was common knowledge that Dorothy only had eyes for the Nigerian pastor, so Precious struck her off the list. But what about Eunice Matabela, the new school principal? Teacher spoke of her often and with admiration. Eunice was married, not that it mattered these days. If not Eunice or Dorothy, could it be that Venda girl in Grade Twelve, the one whose parents paid Teacher to give her extra maths lessons after school? She was tall and sullen with a body that spoke more than she did, the sort of body a man liked. Precious was still trying to remember her name when Jabu’s voice rolled through the gloom.

‘She is here.’

Confused, Precious glanced quickly behind her. ‘You mean Karabo? But she’s not a woman, she is my daughter.’

‘I have answered your question,’ Jabu said firmly. A fly whisk appeared in his hand and he began to beat himself gently about the shoulders with it.

Precious thought the firmness of his tone was ironic for Jabu had never been able to answer any questions at school.

‘No, you are mistaken. Karabo is not to blame,’ Precious said anxiously. ‘She is only a child.’

‘There are no children in this house,’ Jabu said and a chill ran down Precious’s back. Then he dipped his hand in the cup and flicked his fingers at her again. The water tasted like it had been drawn from a dark and ancient well and this time Precious wiped her face with the back of her hand. She had been hoping Jabu would tell her something else. That it was indeed Dorothy Mpetla or Eunice Matabela who was the cause of her troubles. Or the Venda girl with the long slim legs whose name she couldn’t remember. She’d rather it was one of them instead of Karabo. It would have been much easier that way. She felt angry and bewildered and ashamed, all at the same time. She couldn’t bear to think of what Jabu had just said, for how does a mother denounce her own daughter?

Then Jabu lit a small candle and she was grateful for that because the room had grown so dark she could hardly see him. But when had he unzipped his overalls? His bare chest glimmered in the candlelight. His breasts were a size larger than hers and his belly sloped forward, coming to rest in a contented heap between his legs. At school Precious used to tease Jabu about his weight. She hoped he didn’t remember.

Suddenly, he tossed a broken piece of mirror across the mat towards her. It lay there, glinting wickedly, like a sliver of a star that had somehow fallen from the sky. Precious looked down at it, not knowing if she should pick it up or leave it where it fell.

‘She will go back to her people,’ Jabu said.

‘Which people?’ she cried. ‘Go back where, Jabu?’

He grunted and pointed his fly whisk above his head. Precious looked up but all she could see were the shadowy traces of wooden beams.

She didn’t understand. ‘Must my daughter climb up on your roof?’ she asked.

Jabu began to beat himself about the shoulders with the fly whisk again. He didn’t say anything else. It looked like he was done. That was the problem with amagqirha, Precious decided. You never knew what you would get. She sighed and tucked a R50 note under the corner of the mat. As she got to her feet, Jabu flicked his fly whisk at her. She was dismissed.

Precious felt a little cheated that Jabu hadn’t bothered to change out of his overalls. The last time she’d seen him he’d been wearing a grass skirt with leather amulets tied around his biceps. At least he could have messed up his hair a little.

‘You have come.’

His voice was deep and resonant, just how igqirha’s voice should be.

Precious smiled. Perhaps she’d get her money’s worth after all.

‘What brings you here, my daughter?’

She wished Jabu wouldn’t call her that. He'd been two classes behind her at school. She shut her eyes and tried to focus on the fact that he was igqirha now, at least when he wasn’t cutting grass for the municipality.

‘You know why I am here. It is my husband.’

She thought his eyes glimmered but it was difficult to tell in the half light.

‘The teacher?’

‘Yes – Teacher. My husband.’

Jabu bent his head and stirred the beads with a dry twig. Then he dipped his hand into the cup of water and, without warning, flicked his fingers at Precious. She recoiled and cried out in alarm, feeling strangely humiliated, as if he had spat at her. But she did not dare wipe her face.

‘Does he know you?’

‘What do you mean, Jabu? He is my husband. Of course he knows me.’

Jabu slipped his hand between his legs and cupped his crotch.

‘My daughter, I asked whether your teacher knows you.’

Precious’s face burned with shame at the turn Jabu’s questions had taken.

‘No, Jabu,’ she said quietly. ‘Not for several months.’

He bent his head again and rummaged among the items on the mat. His hands were dry and covered in small scars. He muttered a few words to himself, then handed Precious a brown kidney-shaped nut.

‘Eat,’ he said,

Precious reached across and took the nut from him, taking care not to let her hand touch his. When she bit into it a peppery taste flooded her mouth. Jabu watched her carefully until she had swallowed the last piece.

‘I see the cause of your troubles, my daughter.’

‘Tell me,’ she said eagerly.

‘It is a woman.’

What woman? Did Teacher have a girlfriend? Precious ran through the women she’d seen around Teacher, scoring them against their likelihood of mischief. She didn’t trust Dorothy Mpetla. The bitch read the notices in church and spoke isiXhosa like an Englishwoman, clicking her tongue in all the wrong places. But it was common knowledge that Dorothy only had eyes for the Nigerian pastor, so Precious struck her off the list. But what about Eunice Matabela, the new school principal? Teacher spoke of her often and with admiration. Eunice was married, not that it mattered these days. If not Eunice or Dorothy, could it be that Venda girl in Grade Twelve, the one whose parents paid Teacher to give her extra maths lessons after school? She was tall and sullen with a body that spoke more than she did, the sort of body a man liked. Precious was still trying to remember her name when Jabu’s voice rolled through the gloom.

‘She is here.’

Confused, Precious glanced quickly behind her. ‘You mean Karabo? But she’s not a woman, she is my daughter.’

‘I have answered your question,’ Jabu said firmly. A fly whisk appeared in his hand and he began to beat himself gently about the shoulders with it.

Precious thought the firmness of his tone was ironic for Jabu had never been able to answer any questions at school.

‘No, you are mistaken. Karabo is not to blame,’ Precious said anxiously. ‘She is only a child.’

‘There are no children in this house,’ Jabu said and a chill ran down Precious’s back. Then he dipped his hand in the cup and flicked his fingers at her again. The water tasted like it had been drawn from a dark and ancient well and this time Precious wiped her face with the back of her hand. She had been hoping Jabu would tell her something else. That it was indeed Dorothy Mpetla or Eunice Matabela who was the cause of her troubles. Or the Venda girl with the long slim legs whose name she couldn’t remember. She’d rather it was one of them instead of Karabo. It would have been much easier that way. She felt angry and bewildered and ashamed, all at the same time. She couldn’t bear to think of what Jabu had just said, for how does a mother denounce her own daughter?

Then Jabu lit a small candle and she was grateful for that because the room had grown so dark she could hardly see him. But when had he unzipped his overalls? His bare chest glimmered in the candlelight. His breasts were a size larger than hers and his belly sloped forward, coming to rest in a contented heap between his legs. At school Precious used to tease Jabu about his weight. She hoped he didn’t remember.

Suddenly, he tossed a broken piece of mirror across the mat towards her. It lay there, glinting wickedly, like a sliver of a star that had somehow fallen from the sky. Precious looked down at it, not knowing if she should pick it up or leave it where it fell.

‘She will go back to her people,’ Jabu said.

‘Which people?’ she cried. ‘Go back where, Jabu?’

He grunted and pointed his fly whisk above his head. Precious looked up but all she could see were the shadowy traces of wooden beams.

She didn’t understand. ‘Must my daughter climb up on your roof?’ she asked.

Jabu began to beat himself about the shoulders with the fly whisk again. He didn’t say anything else. It looked like he was done. That was the problem with amagqirha, Precious decided. You never knew what you would get. She sighed and tucked a R50 note under the corner of the mat. As she got to her feet, Jabu flicked his fly whisk at her. She was dismissed.